![]()

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

In different ways, you both seem invested in discussions involving objects and images produced explicitly for our consumption – commodities that are manufactured, branded and massively marketed to us. If we pan out there is, of course, a long history of artworks using consumer-based objects and images, sprawling from the readymade, synthetic cubism, surrealist collage, arte povera, pop, neo geo and now to our extended epoch of appropriation. Yet this trajectory, leading through appropriation, seems to be shifting, naturalizing into another ethos entirely, one not born in resistance to appropriation, but one that has so fully absorbed its teachings that objects and images designed within corporations and factories are now just other objects – substances – living in a dense, sometimes delirious field of other objects. We can view this consumer class of object (from to iPads to Adidas shell toes) as having certain diegetic and extra-diegetic properties just as other unbranded commodities do such as an olive tree, a copper plate, a clay brick, a beta fish, a kiwi fruit. I bring this up to begin because some of the basic ways artists seem to be inviting objects into their work seems to be shifting. These changes seem important to recognize and start to shape a parallel universe where artworks might be asked to perform more speculative tasks and rituals.

TIMUR SI-QIN

I think that’s an excellent way of putting it. A shift is happening in which the hierarchy separating natural and manufactured objects is dissolving. This shift is a conceptual deanthropocentrification since in reality humans and their material outputs are just as much a part of nature as termite mounds and seashells. The idea of a separation between the synthetic and natural is a religious conceptual artifact (God having created the separate categories of animals, man and woman.) I think one thing that is allowing this shift to take place is the slowly building understanding that the consumer-object world is largely governed by uncontrollable, non-agential, natural emergent forces rather than any particular ideologies. Or maybe I should say that ideological forces are emergent, causal and natural forces in and of themselves.

PABLO LARIOS

I think it’s difficult to historicize the shift you allude to, Michael, though it is clear to me that we see traces of changes in the relationship between commodities and objecthood on the one hand, and objecthood and the work of art on the other. This goes beyond the platitude that every work is also a commodity; more pernicious is the reality of situations like the merging of production and consumption, changes in the way knowledge is acquired and monetized, shifts in the distribution of images, or the nature of images altogether (maybe all images, insofar as they’re convertible to 1’s and 0’s, are simultaneously texts, too.) The very phrase ‘nature of commodities’ would have once sounded like an oxymoron, but I’m not sure it is anymore. (At least, no more so than Marx’s likeness of the commodity as a kind of upside-down, or dancing, table. Marx could only approach what was lifeless (un-natural) by animating it, turning it into a kind of animal:

The form of wood, for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless the table continues to be wood, an ordinary sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will.

Another way I notice such a shift, at least in how it relates to art, is in the way ‘appropriation’ seems inapplicable – or at least applicable only incompletely – to works such as yours. The works clearly bring in commodities in a way that once would have been categorized as appropriation. But, as I’ve written before, ‘appropriation’ as such is no longer a stable concept because of shifts in how labor is performed and conceived of. Appropriation as a concept – as a ‘making proper’ what is initially exogenous – reflects a model of working that maintains the ipseity, the self-sameness, of individual agents. I think agency has, quite recently, changed; as agency changes, appropriation begins to appear simplistic because the model of agency it is predicated on is itself outmoded, or at least simplistic.

Just look at our very lexicon: referred to recently as several things: appropriation, recontextualization, détournage, or, as far as the shift in labor practices go, as a shift toward ‘collaborative’ modes, i.e. real-life social networking. I think it’s too soon to say, too early to historicize it; I just feel that the concept has cracks in it. Just look at the eye-rolls the very word ‘appropriation’ tends to produce. As far as a divide in nature/manufactured objects, it’s clear that this is in a state of flux (maybe it always has been).

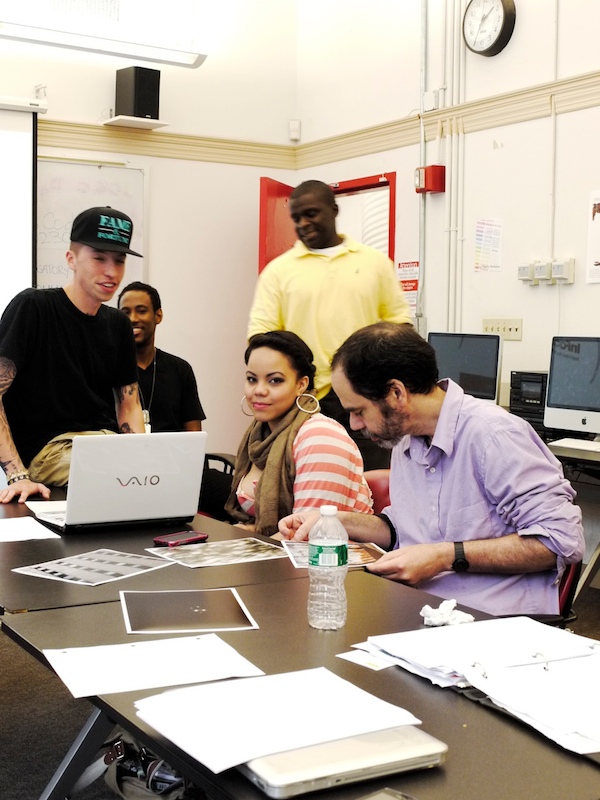

![Michael Jones McKean]()

Michael Jones McKean

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

I agree it’s weird to historicize topics so alive in our here-and-now. In terms of history, my opening comments were more aimed to suggest that these canonical, heritage-y terms are feeling shopworn, a little tired as active placeholders for what seems to be happening on-the-ground level within cultural production. I think we are mostly in agreement here, Pablo. It’s like after the initial hedonistic blowout of appropriation proper, people slowly forgot who the party was for, but decided to stick around anyway – drinking it up. I think some folks are waking up from the binge now, but with a special clarity achieved only through over-exposure. What’s emerging is not a ‘kill your father’ militarized evolution, but something achieved more silently, gradually – overnourishment breeding special adaptations.

Following up, Timur, yes I agree, we’re in some kind of corrective crawl, mending a lived-through myopia extending back to the notion that our earth must be the center of the universe – a kind of ultimate anthropocentric view. But as we embrace more deeply de-anthropocentrification as an ethos, say for instance within the refinements to the various realist camps and speculative movements, one would imagine we might find ways to re-plug into an equally robust, parallel discussion on ethics. I’m curious if the discussion could become more strange and more generative if a space for verbs, perception, feeling, romance could also open up, making space for a fully emergent and complex form of humanism. In some ways I see this as a classic function that artists have been involved with – borrowing some of the more utilitarian straight-talk within the hard-humanities and scientific communities and extending these findings to some other, totally speculative place, one not so singularly beholden or dogmatic.

TIMUR SI-QIN

When thinking about ethics in relation to art I usually have this to say: Art is not directly constrained by ethics; but artists are humans and humans are social-primates who have evolved ethics as an adaptation. In this way, art is indirectly constrained by ethics. I think a form of ethics based on emergence would be coming from sociobiology/evolutionary-psychology. Since the emergent system that is at play would be the human system and it’s emergent and historically evolved social morphologies.

PABLO LARIOS

Timur, you align yourself with biological and ecological models; both of you adhere to the tactility of certain objects, and play off the semiological resonances of imagery familiar to us through our everyday consumer experience, but also through all that is “massively marketed” to us. The artist, like a consumer, is choosing between materials; like a character in a video game, adapting different skins or even discrete/conflicting avatars…

One thing I tried to stress in my piece is the reciprocal relationship that consumers and corporations now have; the person has become the product; this is something reflected in micro-advertising tactics – entire markets are developing. Corporations create markets; they don’t simply fulfill them.

Art-historical models can both predict this and seem to go blank on it as a subject. The entire lexicon, inherited from Marxism and capitalism dually, of ‘commodities’ and ‘consumers’ has already fallen apart. … the prosumer, the unreadymade, the neo-material, these hybrid formulations point to an inadequacy in the terminology we’ve inherited from outmoded economic models.

In the same way that certain art objects can simultaneously embrace ‘the market’ and, in discrete instances, seem to offer up resistance to it. The dualities in you guys’ exhibition, the contradictions at play (death as a form of love, say), seem to embody this.

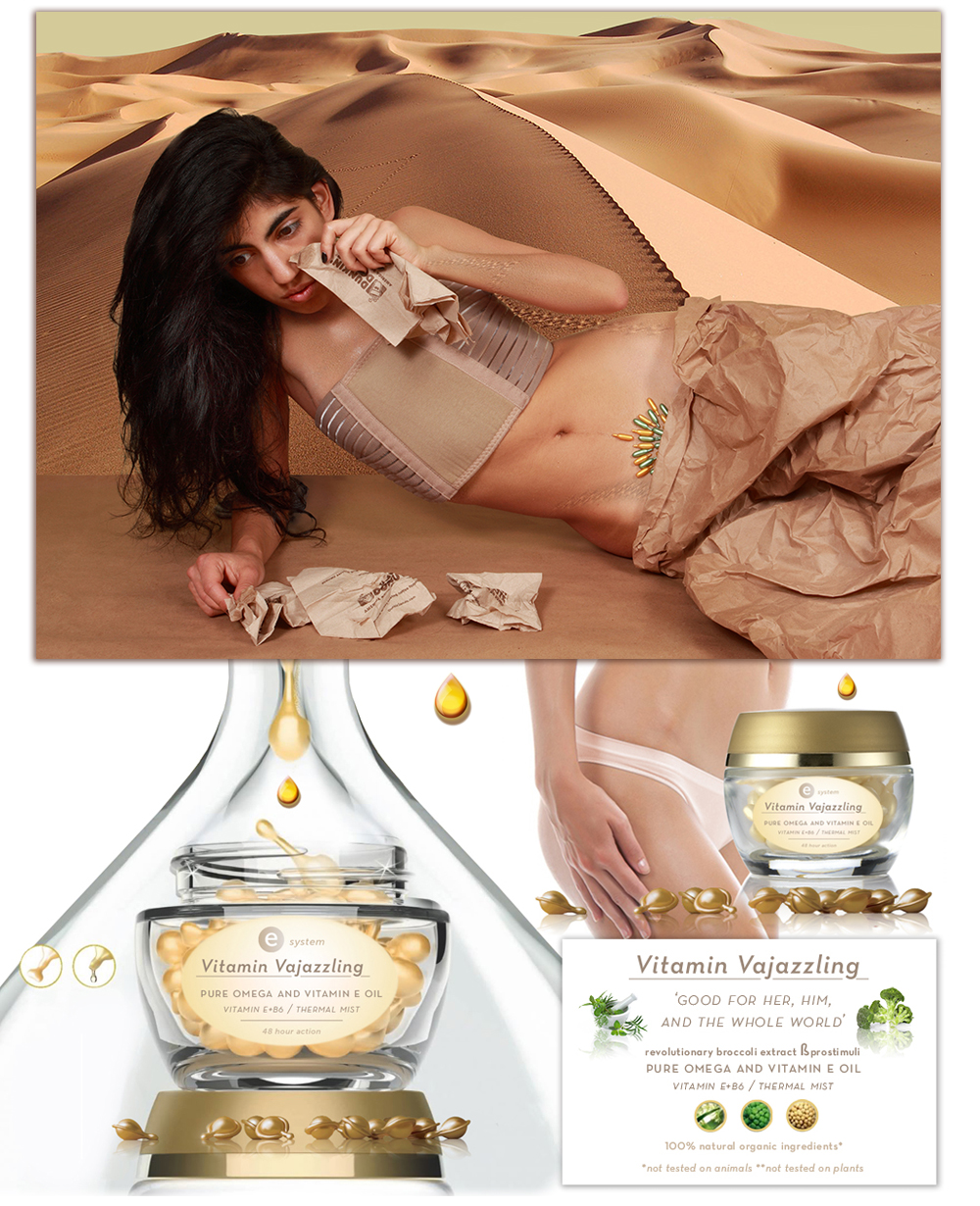

![Timur Si-Qin]()

Timur Si-Qin

TIMUR SI-QIN

Right, the mistake that Marxist materialism made was to make labor the only material that mattered. When in reality, actual materials and their properties, like copper, wood and oil are the real driving forces of the world. Also Manuel De Landa has argued, via economic historian Fernand Braudel that the term “Capitalism” is also only a reified generality that does not actually map to reality. That is, there is no “capitalist” system; there are many emergent heterogenous economic systems alive in the world. Some are more fair than others. But all are predicated by the biological constraints of the body, that we need food, water and shelter, and because we are social animals these are provided to us through systems of exchange with conspecifics. This is why it is irrational and I would argue also an ascetic religious notion to think that we can or should ever escape “the market.” After all it is ultimately economic forces that drive the form of all things, from a frog’s leg to the shape of a leaf.

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

Pablo, when you mention that the lexicon of Marxism and the trusted relationship between commodities and consumers has weakened – perhaps its important to also claim with certainty, and total inevitability, that these sacred concepts are really only momentarily useful to us – with time, they will indeed all fail. I agree with you, to me these kinds of terminologies are feeling more and more outmoded – ill – perhaps in a similar way the quickly evolving discussion surrounding real and virtual now seems, by all measures, quaint, totally nostalgic. To me, thinkers like De Landa don’t necessarily lead us out from the hegemony of these models, but they might be pointing toward possible exits.

Not to overly romanticize art making here, but in relation to this topic, the field feels open and exciting as a site to model some of these ideas in a more skewed, malleable way – one not so fixed to a prescribed utility. With De Landa, one of the reasons I think he’s so often brought up in artist circles is the almost psychedelic nature of his thinking, there are these nutritious parallels: the expansion and compression of scales, peripatetic wandering over ages and regions, the fluidity between disciplines. Moreover, the basic supposition of a mind-independent universe, a precept he reminds us of repeatedly, is at its core empathetic. It evokes a solidarity with things – this is deeply abstract, a kind of ethics in and of itself.

PABLO LARIOS

As far as ethics go, works such as yours seem to draw a particular, peculiar form of power in that they seem to underwrite an ethics. If, as I said earlier, shifts are occurring both in what constitutes ‘nature’ as well as in how agency is conceived of, then both of these changes imply shifts in power relations and, by extension, ethics (insofar as ethics concerns itself with economies of power).

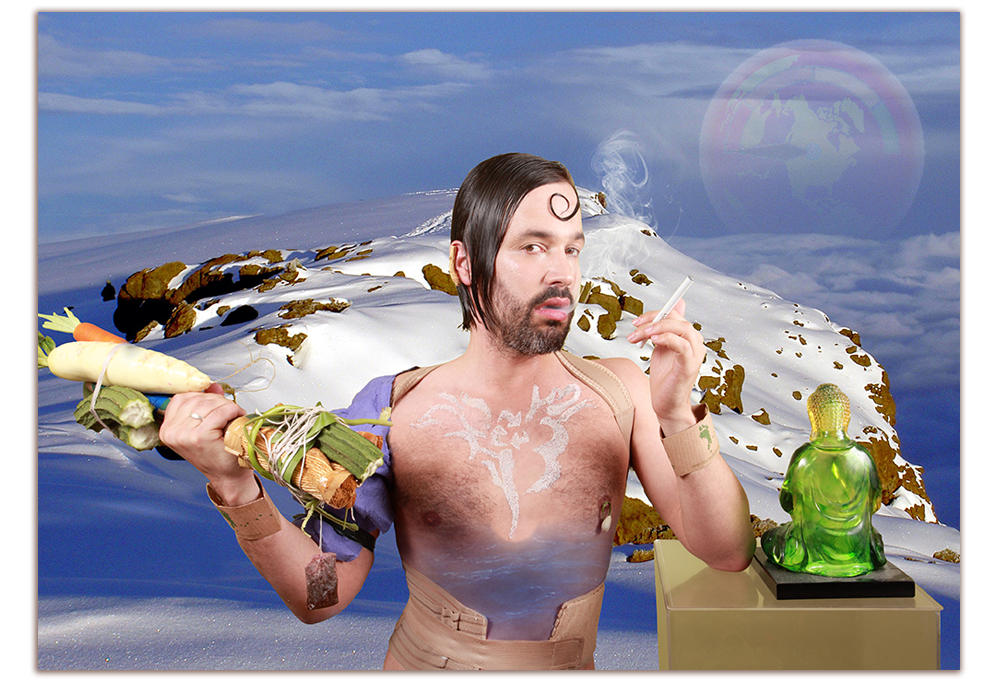

![Michael Jones McKean]()

Michael Jones McKean

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

I like this idea of what ‘underwriting an ethic’ might be. Maybe there is a way to parlay this talk of ethics to another topic that drifts in and out of the exhibition – definitely in Timur’s project – violence as a concept. Perhaps the comparison is too abstract, but it makes me think about Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown – a truckload of hot asphalt dumped down a ravine, this sweetly fucked up move. Or watching his film Spiral Jetty and being overwhelmed with long, slow-mo takes of roaring diesel engines, huge machines billowing black fumes, tractors pulverizing and dumping load after load of stone, helicopters cutting up the air while circling the spiral – all this aggression played out within an immaculate landscape. The assault becomes even more aggressive, more forceful, and more punk when contextualized against the historical backdrop of rising, almost militant, environmentalism. In this sense, Smithson’s work embodies an ethos that is so blatantly counter to a pervasively liberal, socially conscious mentality. I’m curious how you think about all this in your work that often uses objects of warfare: compound bows and gauntlets, swords, armor and guns leading to this exhibition with burnt and melted yoga mats – an action when perpetrated on a body-sized artifact like a matt – one can’t help but sense violent undertones.

TIMUR SI-QIN

Violence is a theme that is hardwired in us to be relevant. The reason violence and romance are such dominant themes in narrative and entertainment is because they are innately relevant themes to us as biological replicators, e.g. natural selection and sexual selection. What I find extremely interesting in activating these evolutionarily relevant themes is that they provide us with information about the deepest questions one can ask: Who are we? How did we get here? Because truthfully there was a real way that the past happened in order to form the present and influence the future; namely, the universe evolved via causal, historical, and material events.

So in that way the dominance of violence as a theme in narrative can be seen as the fingerprints of evolution itself. The faint cosmic afterglow of all that has happened before.

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

Yes, I totally agree. When we zoom out far enough, all the details of living, all the crisscrossing minutiae of day-to-day life get swallowed up and absorbed by causal, almost predictable sequencing. Subtle textures of life suddenly look pre-determined, our choices silently administered by precisely metered chemical spills in the brain – chance becomes an algorithm. So when we feel the sensation ‘love’ – this palpably real bond to another – we’ve slipped into ancient, alchemic communion with our ancestors lured into the beginning stages of an unbroken continuum of procreation that the emotion ‘love’ (or the chemicals that induce its sensation) has tricked us to enable. Or violence as it has been sublimated into sports and feats of risk and peacocking – still by and large wedded to sorting out gene pool selection. As a model, in its consistency there is something totally reassuring about acquiescing to something primordial, causal, genetic. But I can’t help but flip it, or at least try to make it more personalized, local, wayward. We build a life out of an aggregated chain of brief moments: anxieties, sensations, dreams, conversations, objects, choices, people, carnal pleasures.

Getting more specific, if we can use violence as a pivot, I like to think about the subtle inflections, the huge spread of tonality in the way cultural producers decide to represent violence to us and in doing so, tell us very different things about ourselves in the process. So Spring Breakers and Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 3D and Django Unchained or Haneke’s Funny Games all depict violence, but they report to us in vitally different ways, so much so that even as the subject matter of each film may have something to do with violence, the actual carried-away content of each film is vastly different. I’m curious about this in your work, so even if love and violence might be some of the themes operating more globally in the work, the objects come to us delicately, metaphorically, materially – bound to their own internal logic.

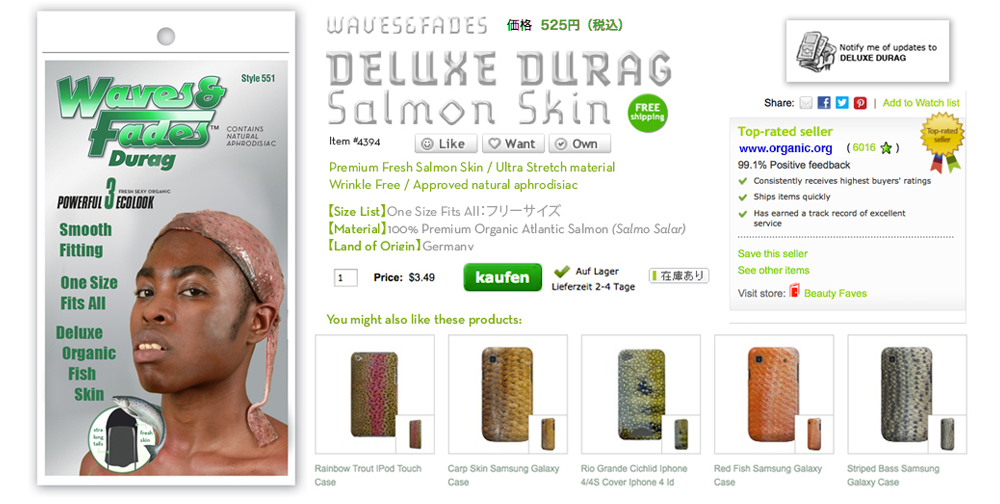

![Timur Si-Qin]()

Timur Si-Qin

TIMUR SI-QIN

I think violence is somehow fundamentally about confronting the body with it’s own materiality, however I think it’s interesting that violence comes across at all. After all it’s only a single sheet of PVC plastic that has been burned. But through memory associations we relate the plastic to bodies and people that have been materially compromised in some way. I think that tenuous connection from concrete to abstract thinking is fundamental to the way art is processed.

But coming back to what Michael was saying about determinism and causality. One thing I think should be pointed out is that determinism does not preclude free will. In fact completely causal systems whose complexity passes a certain and (low) threshold will behave in ways that cannot in principle be predicted nor computed. Yet these same unpredictable complex systems (which most systems found in the real world are) are still highly structured displaying deep and elegant patterning. Just think of the patterns exhibited in plants and animals (which happened to be the last subject of study of the brilliant Alan Turing before he was driven to suicide for being homosexual in 1950’s Britain). This simple fact about causality leaves plenty of room for free will, which itself is an emergent adaptation of life. It is why nature is so beautifully patterned yet inherently unpredictable.

PABLO LARIOS

I think it’s interesting that you guys have touched on the symbolic potential of violence – violence as association, as material, that is, as a sign. In a way, this is a theme that’s linked very closely to evolution. “Violent” objects – whether artworks or artifacts from nature – might seem marked as falling on either end of the same temporal spectrum. I mean simply that there’s a weird temporality implicit in this scheme. Take something like a warning sign: it points forward (if you do X, Y will happen), proleptically; whereas something like a broken windshield points backward (analeptically, X has occurred). Maybe these serve specific functions on the evolutionary scheme: the horns of certain animals – surely as symbolic as they are functional – vs. the ritual stigmatization of objects of violence (the “spoils” of war). Beware the horn for what could happen; avoid the spoils because they already are stigmatized.

I would argue that there’s not only a temporal split here, but also a subject/object split: the subject of violence points forward, into the future, whereas the object of violence points backward, into the past, as victim. Clearly there’s a certain tribalism/primitivism in these dichotomies. Some of this might seem ‘problematic’, dualistic. I still think it’s worth it to explore. I still maintain that our choice of examples is slightly humorous.

Maybe primitivism is the dark side of any scheme that relies on evolution. Maybe a ‘lighter’ side is how this relates to anthropology. One might see evolutionary schemes as much in something as benign as table manners as in the typology of warfares.

![Timur Si-Qin]()

Timur Si-Qin

TIMUR SI-QIN

Can you clarify how subject/object and future/past implies primitivism?

PABLO LARIOS

It might not: I just think it’s interesting that the setting for our discussion is a kind of primitivist landscape, with its talks of violence, evolution, and nature. There’s an interesting legacy of artists adopting primitivist frameworks, and I’m interested in pressing you guys on this a bit. It’s not necessarily the dualities (subject, object, future, past) that imply primitivism, it’s the color of our metaphors, the language with which we approach the works. One might also say that it’s not strictly a regressive primitivism, but the temporality is split: it’s a primitivism that implies the future as well as the past, a kind of techno-primitivism.

In a way, the burnt yoga mats in your exhibition invoke a fitness-ready positivism, an embrace of the eating, sex-driven body you mention; the presence of charcoal suggests a desire and necessity for foodstuffs, but in the most base commercial form (“no lighter fluid needed”); the decapitated head, the color grid existing in a kind of – I agree this is all complicated, tense, and contradictory. The temporality of these pieces is both medieval, at times – the head looks like a kind of war trophy – yet indelibly tied to the way we can imagine our futures. These contradictions are not crinkles in our thought; they are constitutive of it, they are markers for the tense and opposing modalities in which we imagine reality in general. So we have it that your works look both futuristic and medieval, just as the deep sea looks like a version of outer space, and outer space looks like a TV show; certain Egyptian pyramids look futuristic (the imagery of the Vulcans in Star Trek clearly draws on this). Isn’t this role-reversal a sci-fi trope anyway? I think of the cave like, Neanderthal-era imagery in The Matrix Reloaded (the fictional city called Zion), or the pervasiveness of our association of alien themes and native American themes (in the X-Files, say): both contain colonial narratives and stories of historical abduction.

TIMUR SI-QIN

The thing I’d like to point out is that the methods by which objects are interpreted is largely a priori to culture or ideology. The tenuous link to violence that a burn mark on a sheet of plastic makes is most likely the byproduct of a neural architecture that has been in development for millions of years. As the evolutionary psychologists Tooby and Cosmides point out this would explain why in popular media things like attacks by predatory nonhumans, chase scenes, physical violence and blood revenge are so over-represented even if they are no longer a part of and even counterproductive to everyday life.

I think when it comes to the question of why casting art in terms of evolution or evolutionary psychology is important in the first place. I would say that to do otherwise is almost a kind of myopia on the becoming of humanity, or even worse a sort of post-modern creationism. Evolution is the only known causal mechanism by which functional relationships can arise that are more highly ordered than chance. And since our bodies, minds and societies belong to this set, it’s safe to say that everything shaped by humans is ultimately shaped by the events that shaped humans themselves.

Along with the purely philosophical necessity of an evolutionary lense comes a framework from which to understand and analyse artworks, artists and even the art market in ways that more entrenched art historical perspectives are unable to do. Questions such as why art occurs in all human cultures, or why art can stir strong emotions in the first place, since emotions are evolved to signal that something is important to an organism. An evolutionary framework is non-arbitrary and, dare I say, true. As true as the fact that we are related to all other life forms on earth.

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

Going back to where Pablo began, the subject of primitivism is really interesting, I just have trouble investing in a style of thought so classically reductionist, so binary. I’m curious how one might build a working model that instead seeks out complexity as a driving ethic – one that embraces a more kaleidoscopic, long-view of events and objects and materials. In terms of a long-view, I can see how primitivism (and I’m really curious about this term techno-primitivism which seems to flank primitivism-proper in a more satisfying way) might be a convenient way into the discussion; especially one that until now has largely focused on violence. But violence as we’ve been discussing it is really just a proxy for a whole set of ancient baselines that stay close to us through time, acting as central pivots. So, over time our tools change, but the impetus to make new, more effective tools does not. The norms and ethics around sex, sexuality and procreation continue to change, but our desire to have sex does not. The food we eat and the techniques used to prepare our food shift with the times, but the need to consume foodstuff does not. Through medicine and genetics we are living longer, but we still confront death. The styles of our dwellings change, but the basic need for shelter is fixed, and on and on… These could seem primitivistic to some, but to me feel way more complicated, fraught, contemporary, and ultimately more realist in its perspective – more ontologically independent.

Very much related, I feel its important to press you, Timur, on evolution as an agent potentially leading us out of a post modern stalemate – I think its really exciting on many levels, but also can feel forced, synthetic – unable to completely service a world with substances as well as sentient beings. Moreover, as a model it seems to prematurely duck-out against a rhythmic progression toward maximum complexity – some kind of ad-hoc Omega Point – one that our continuum of modernisms, each one a corrective for the shortcomings of the last, seems to chart for us; an evolutionary process in and of itself. The success of the evolution-meme shows us that it continually satisfies, giving us enormous security that our world is patterned, inter-connected and distantly knowable. Yet counterintuitively, in its thirst to show us the origin depths of all being, to sweetly explain universal causality, evolutionary thinking seems only able to satisfy us superficially as people. For it to be real, useful, evolutionary thinking should be an option within a larger network of thought models – a kind of synchronistic, see-through, meshwork of tools and ideas. The trouble is, as viable options are shelved in favor of a single unifying rubric, things begin to sound like religion – but religion in drag. All this is to say, evolution is a consistent, reliable drum beat, but not really music. Or, as a lense it can deftly describe how things are, but never begin to describe how things feel, or appear.

![Michael Jones McKean]()

Michael Jones McKean

TIMUR SI-QIN

My interest in evolution has two primary entry points and maybe by disambiguating them I could hopefully address these very good issues Michael raises. The first entry point is evolution as an umbrella term to refer to the fundamental morphogenetic process and potential of the material world. Going beyond the domain of biology, this slightly more abstracted idea of evolution is based on the recognition that like biological evolution, change itself is a form finding process. The change in matter, in information, in stars, universes, quarks, dogs, memes and crystals all occurs through the morphogenetic potential of matter. What unifies the change in all these things and validates the use of the blanket term ‘evolution’ is that their morphogenesese are the results of causal form finding processes just like, and identical to, biological evolution. In fact it is causation itself, the simple relationship between cause and effect, that underlies and unfolds into biological evolution as well as all pattern in the universe. The very same process that sculpted the stars also formed DNA, Humans, Operas, and Opera houses. However, whether one believes in causality or a mind-independent material universe in the first place is another debate at the heart of philosophy, the debate between ‘realism’ and ‘idealism.’ The validity of these positions ultimately rests on which side of this debate one lands. If the structure and patterns of the universe exists outside of our minds, before and after our lives, then evidence tells us that universal form finding processes underlie the formation of all matter and experience in the universe. If the structure and patterns of the universe do not exist outside of consciousness then the very notion of evidence is called into question.

Post modernism as a fundamentally ‘idealist’ philosophical position arose as a need to counter the meta-narratives of modernity. Religion, fascism, colonialism all committed atrocities in the name of their respective meta-narratives. Post modernism, as a reaction, abolished the notion of an ordering meta-narrative and in doing so abandons the notion of a mind-independent objective universe: there are many subjective truths none more true than another. But from the standpoint of realism, this was an over-correction in response to modernity’s failings. A conceptual safeguard that functions with the premise that in order to prevent a false claim of truth (and by extension its consequences), the very notion of truth is abolished, or to a softer degree, access to truth is unattainable. To back up this claim is the idea that since no-one got it correct in the past no-one should claim a truth today, e.g. nazis, copernican revolution, etc… That science or the measure of truth is a construction much like religion or any other worldview. But just because the geocentrism that Galileo challenged was untrue, does it mean that Galileo’s heliocentrism is equally untrue? The problem this argument faces is that it is based on inductive reasoning (e.g. All swans we have seen have been white; therefore all swans are white). It also abandons the idea that truth can be approached, or resolved even in degree. Which renders unintelligible the predictive capacity of science and the ever increasing degree to which materials can be manipulated.

The second entry point into evolution comes from the need to bridge this more cosmic and philosophical notion of morphogenetic causation to art. If one holds a mind independent, causal reality to be true then how does one address the morphology of art? Since art is a product of artists and specifically the thoughts of artists, and artists are humans whose brains are as much a product of causal material evolution as are their thumbs, then evolutionary psychology is the realist-materialist bridge between the morphogenetic potential of matter and art. Evolutionary psychology is more a lens than a branch of psychology and is according to evolutionary psychologist David Buss:

“based on a series of logically consistent and well-confirmed premises: (1) that evolutionary processes have sculpted not merely the body, but also the brain, the psychological mechanisms it houses, and the behavior it produces; (2) many of those mechanisms are best conceptualized as psychological adaptations designed to solve problems that historically contributed to survival and reproduction, broadly conceived; (3) psychological adaptations, along with byproducts of those adaptations, are activated in modern environments that differ in some important ways from ancestral environments; (4) critically, the notion that psychological mechanisms have adaptive functions is a necessary, not an optional, ingredient for a comprehensive psychological science.”

I think this last premise might speak to the point that Michael makes about the evolutionary lens as “an option within a larger meshwork of thought models.” Or rather that it is not an option given a realist-materialist understanding of the natural world. However despite its necessity it also does not necessarily negate other tools or thought models either, with the understanding that tools and thought models themselves are a product of historical, biological, material and causal form finding processes. I hope this explains how an evolutionary lens is not a replacement of other tools of thought, but a necessary foundation to thinking about the natural world, which we and everything we experience are a part of.

Resistance to the idea of an evolutionary lens may come from some misunderstandings about evolutionary theory itself. Misunderstandings that equate evolutionary theory with eugenics or social-darwinism which are misunderstandings of evolution themselves. Take for example the notion of survival of the fittest. The idea that natural selection ordains the strong to dominate over the weak. Fitness in the biological sense does not necessarily mean strong or physically fit but instead refers to the differential reproduction of genetic traits however that may happen. A lion is not better or stronger evolved than an earthworm, instead they are independently and equally evolved for their respective environments. Another misunderstanding of ‘fitness’ is the idea that there is one perfect ‘fittest’ solution and it’s imperfect copies. In contrast evolution requires variation in order to function. So if one were to imagine evolutionary solutions they are never a single perfect individual but rather a dynamic population of variation. There is no perfect platonic zebra and many imperfect copies, instead there is a constantly evolving variable population of zebras in dynamic interplay with their environment.

![Timur Si-Qin]()

Timur Si-Qin

MICHAEL JONES MCKEAN

You covered a lot of important territory, and for the most part I don’t disagree at all with what you’ve laid out. These ideas are so clearly defined to the point of being non-negotiable – like arguing against the grid as a capable compositional device – it just works. My issues stem from limitations the concept imposes on modeling full-bodied, and at the risk of using your word, truthful registrations of thingness – one where more sleepy, mezzanine levels of reality are called upon to occasionally do some heavy lifting. Take for instance ‘glare’ – glare is very real, everyday, and glare of course exists as something mind independent – its reflective, gleam exists whether or not you or I are around to bare witness. But even with all of glare’s here-and-now qualities, evolutionary doctrine has trouble supporting an interesting, holistic, and faceted philosophy of glare past addressing our eyes and minds as evolved sensory organs capable of perceiving glare, or millions of miles away gravity churning particles into light-projecting producers of glare; or why even suggesting the study of glare might be a beneficially adaptive trait. Yes, sure, but by adapting a strong-arm causal position through the backdoor we shutter-away millions of mezzo levels of information – information that is real but that exists below, adjacent, lateral, inbetween, or just plain outside of causality.

If a working philosophy (perhaps neo-materialist) is to take hold, it doesn’t actually behoove us to edit these levels out because they’re unpleasant or don’t play well within the elegant organizing systems we have designs on. It starts to look like weird intellectual orthodoxy, something strangely totalitarian given the hardscrabble plurality we are emerging from. But more accurately, and maybe worse, the governing logic of any organizing system puts into motion an operational style that slowly erases the possibility of producing rogue structures – in this case extinguishing the very possibility of, say, exploring the intelligence of glare. Here, the editing happened not because we manually pressed delete, but because we couldn’t even see the ships. This is where a mind independent reality – and perhaps old school realist-materialist ideas find a functional limit – because, of course, Columbus’ ships were real.

Maybe all this is too far afield. I wonder if we can dovetail the discussion back to art-making, using it as a basecamp to model some of what’s in the air. This surge in evolutionary thinking to me seems attached to something larger, an upswell of burgeoning ideas that for me bring into focus many good things. So pivoting off evolutionary thinking’s baseline de-anthropocentrification, nearby we might find Speculative Realism or its nerdy brother Object Oriented Ontology. We might also find strains of Techno-Animism, (maybe the cousin of Pablo’s techno-primitivism) like an iMysticism bubbling up from our inability to see, or intellectually grasp the overwhelming complexity of everyday systems and objects (from how my iPhone receives Wifi signals, to a massive meteorite breaking apart over Russia, to the compression strength of neoprene, to the unseen cancer causing agents in eyeliner remover). The backdrop to all this of course being the Internet which asks us to ever more fluidly toggle between a screen-based world and an object based world giving rise to New Aesthetics or Whatever Aesthetics and on and on. Here, art making becomes an urgent, and in many ways a strangely utilitarian, polymathic tool able to build-out some of these ideas – not just offer up more illustrations.

Credits

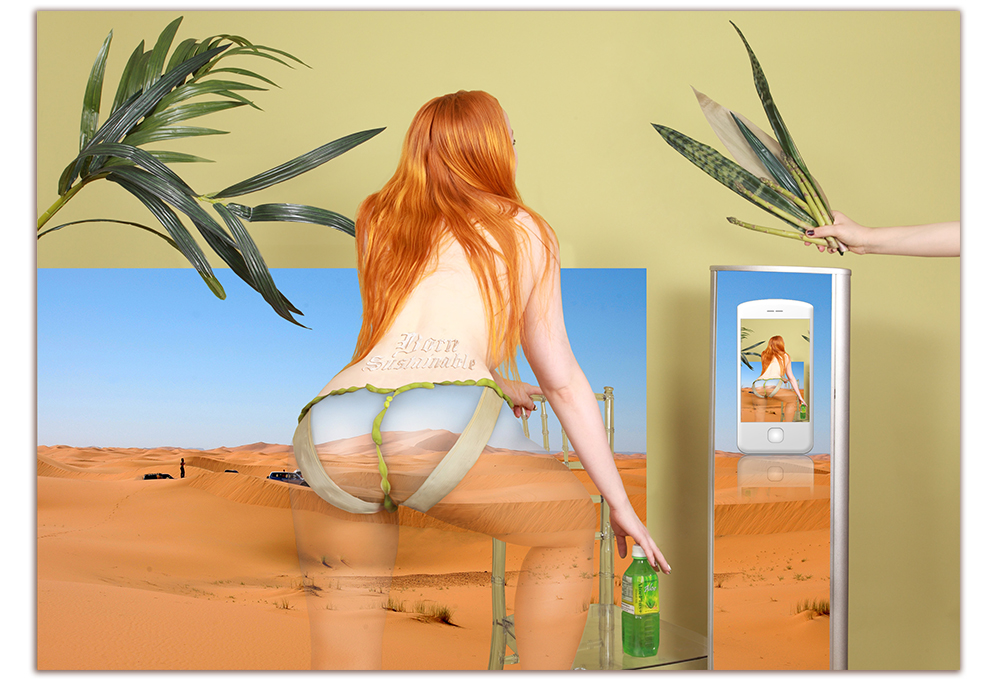

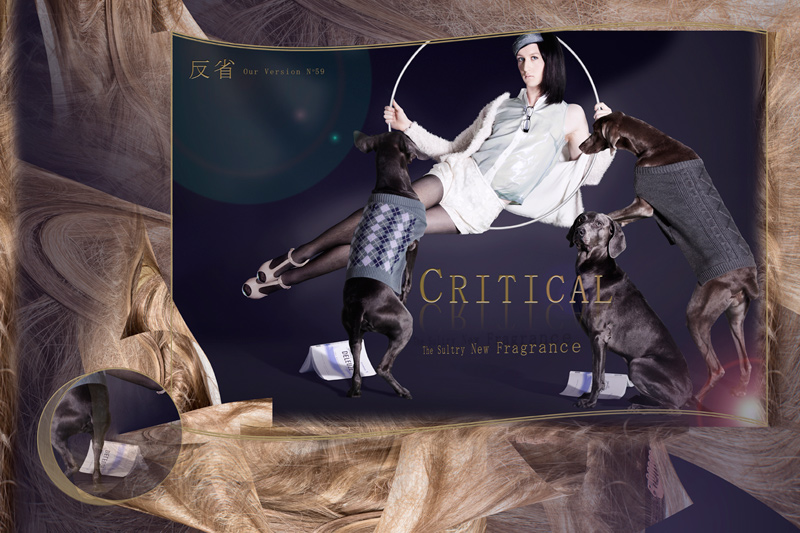

Images Timur Si-Qin,

Love & Resources, and Michael Jones McKean,

The Folklore